Writing Components

Platform for Situated Intelligence applications are composed by connecting components together. A component in \psi is an encapsulated unit of data processing that, in the most general case, takes a number of streams as input and produces a number of streams as output. Many components are already provided with the framework and in time we expect this eco-system to grow -- the whole idea behind \psi is to enable reuse.

This document provides an introduction to how to write your own components. It is structured in the following sections:

- A Simple \psi Component: explains how to create and use a new component, and discusses a number of important aspects about the \psi programming model in relationship to writing components.

- Stream Operators: discusses design patterns around stream operators, which are a special case of components that have a single input and a single output.

- Subpipelines: describes subpipeline components and their behavior.

- Composite-Components: explains how to wrap a graph of sub-components into a higher-level composite-component.

- Registering for Notification of Pipeline Start/Stop: describes how to hook into pipeline life cycle events.

- Source Components: presents design patterns for writing source components, like sensors and other data generators.

- Guidelines for Writing Components: summarizes a set of recommended guidelines for writing component.

This document assumes an understanding of the concept of originating time for \psi messages. To get familiar with this construct, please read first the Brief Introduction and the Stream Fusion and Merging in-depth topic.

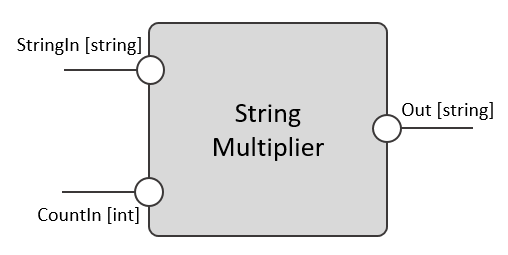

To write a new \psi component, we simply define a .NET class, and create a set of receivers, which model the inputs and a set of emitters which model the outputs. To illustrate this with an example, consider the component shown in the figure below.

The component has two inputs, the first of type string, the second of type int, and an output of type string. We would like this component to behave as follows: when it receives a message on the StringIn input, we would like the component to memorize the input. Then, when it receives a message on the CountIn input, we'd like it to push on the output stream a string that contains the received string, copied as many times as specified in the CountIn message. Granted, this component is probably not very useful, but it will help us illustrate how components are written and a couple of important points about how they function.

Here is the code for the component:

// Implements our new component

public class StringMultiplier

{

// Variable used to store the last input string

private string lastStringInput = "";

// Constructor

public StringMultiplier(Pipeline pipeline)

{

// create the two receivers

this.StringIn = pipeline.CreateReceiver<string>(this, ReceiveString, nameof(this.StringIn));

this.CountIn = pipeline.CreateReceiver<int>(this, ReceiveCount, nameof(this.CountIn));

// create the emitter

this.Out = pipeline.CreateEmitter<string>(this, nameof(this.Out));

}

// Receiver that encapsulates the string input stream

public Receiver<string> StringIn { get; private set; }

// Receiver that encapsulates the count input stream

public Receiver<int> CountIn { get; private set; }

// Emitter that encapsulates the output stream

public Emitter<string> Out { get; private set; }

// The receive method for the StringIn receiver. This executes every time a message arrives on StringIn.

private void ReceiveString(string input, Envelope envelope)

{

this.lastStringInput = input;

}

// The receive method for the CountIn receiver. This executes every time a message arrives on CountIn.

private void ReceiveCount(int count, Envelope envelope)

{

// Compose result using a string builder

var stringBuilder = new StringBuilder();

for(int i = 0; i < count; i++)

{

stringBuilder.Append(this.lastStringInput);

}

// Post result on the Out emitter, carrying the originating time

this.Out.Post(stringBuilder.ToString(), envelope.OriginatingTime);

}

}To define a new component, we simply write a class — in our case StringMultiplier. The constructor takes in the Pipeline object, which will be passed to the component at construction time and allows it to create receivers and emitters. The component defines its receivers and emitters (in our case StringIn and CountIn and Out), as properties with public getters and private setters, using the Receiver<T> and Emitter<T> generic types.

The constructor for the component creates the receivers and emitters by calling the CreateReceiver and CreateEmitter methods on the pipeline object. In both cases the first parameter is the component itself (i.e. this). When creating a receiver, the second parameter specifies a method that will be called when messages arrive at that input. Generally, we refer to these methods as receiver methods. In our case, the StringIn receiver is associated with the ReceiveString method, and the CountIn receiver is associated with the ReceiveCount method. You can name these methods as you see fit, they simply need to be associated with a particular receiver during the CreateReceiver call. Finally, the last parameter in the calls to CreateReceiver or CreateEmitter is a name that will be associated with that input or output.

The signature for each receiver method has two parameters. The first one is of the same type as the receiver, and will contain at runtime the value of the incoming message on the stream. The second parameter is of type Envelope and will contain the message envelope information, including the message originating time, sequence number, etc.

The ReceiveString receiver method simply captures the input message in the lastStringInput private variable. The ReceiveCount receiver creates the corresponding output by using a string builder and appending the stored string as many times as the count input. It then posts the results on the output stream by calling the Post method on the this.Out emitter. The Post call takes two parameters: the first is the message to be posted, which needs to be of the same type as the emitter. The second parameter is the originating time for this message. As explained in the Brief Introduction tutorial and the Stream Fusion and Merging in-depth topic, \psi components propagate the originating times for the incoming messages to the output streams. It is the responsibility of the component author to make sure this is the case and to choose what the originating time for each outgoing message is. In this case, we are choosing to propagate the originating time from the count input as this is what triggers the outputs.

To use this component, we have to instantiate it and connect it into the larger application graph. Here is one example:

using (var p = Pipeline.Create())

{

var strings = Generators.Return(p, "Test");

var counts = Generators.Range(p, 1, 5);

var stringMultiplierComponent = new StringMultiplier(p);

strings.PipeTo(stringMultiplierComponent.StringIn);

counts.PipeTo(stringMultiplierComponent.CountIn);

stringMultiplierComponent.Out.Do(m => Console.WriteLine(m));

p.Run();

}Here we generate a stream of strings that posts a single message "Test" via Generators.Return, and a stream that posts the integers from 1 to 5 via Generators.Range. After initializing the component, we connect the input streams to the component receivers using the PipeTo operator. Finally, we process the component output with a Do operator that simply prints the results to the console.

Next, we would like to discuss a couple of important aspects about the \psi programming model that are fundamental to how components run and are implicit in the example above.

Components connected in a \psi pipeline generally execute concurrently. The \psi runtime controls their execution, by controlling when the receiver methods are called with the next available message.

In this process, the runtime guarantees exclusivity between the execution of different receiver methods on the same component. In other words, if one of the receiver methods is launched, it will be guaranteed to complete before any other receiver method on the same component is invoked. This is an important property, as it generally allows the component developer to write components without concerns about thread safety. For instance, in the StringMultiplier component above, both receivers access the same lastStringInput class member. However, no synchronization primitives are used to ensure exclusivity. The runtime guarantees that whenever the ReceiveCount method is executing, the ReceiveString method is not executing and the other way around. This way, the component state variables (like lastStringInput in our example) are automatically protected. At the same time, when the application is executed the \psi runtime can still schedule multiple components to run in parallel and achieve pipeline-level parallelism and CPU efficiencies, while maintaining this helpful invariant.

There are two additional observations we would like to make in relationship to the exclusivity of receivers. First, the runtime is able to know where to ensure exclusivity, because of the first parameter on the CreateReceiver method. Recall in the example above the lines used to create the two emitters:

// create the two receivers

this.StringIn = pipeline.CreateReceiver<string>(this, ReceiveString, nameof(this.StringIn));

this.CountIn = pipeline.CreateReceiver<int>(this, ReceiveCount, nameof(this.CountIn));The first parameter of the CreateReceiver method (called owner) is an object that informs the runtime that these receivers are owned by the same component. In this case, since we have passed in this, i.e. the reference to the current instance of the component, the runtime will know to execute these methods exclusively on that component instance. If a second component of the same type would be instantiated and connected somewhere in the same pipeline, the receiver exclusivity applies on each of the components separately, but the two components can execute in parallel.

The second observation is more of a programming guideline. Because of exclusivity of receivers, care in general should be taken that the processing code running in each receiver does not take too long, as this would induce large latencies in the pipeline and would also prevent other receivers from being scheduled during that time. The \psi parallel programming model in effect encourages decomposition and encapsulation, and discourages large, monolithic components. Later on, in the Composite-components section of this document, we discuss how to instead construct large components by hierarchically aggregating smaller ones. This not only will foster encapsulation and reuse, but will also enable gains in efficiency via the pipeline-parallel execution afforded by the runtime scheduler.

The \psi runtime uses an automatic cloning system when passing messages around to enable data-isolation between components. Component writers can access, read and even modify the messages arriving inside a receiver method (like in a regular .NET event handler) without worrying about concurrency with other components that may also receive and operate simultaneously on the same message (multiple downstream components can be connected to the same source stream). Each receiver method connected to an emitter gets its own copy of the data that can be read and modified at will throughout the lifetime of that receiver method.

At the same time, once the receiver method exits, the runtime may choose to reuse the memory underneath the message (the cloning mechanism reuses message buffers, in an effort to minimize the number of allocations and garbage collections that happen when the pipeline runs in steady-state). As a result, if the component needs to hold on to a message past the exit from the receiver, the message should be cloned. The \psi runtime provides a general method for cloning .NET objects called DeepClone().

Note: In the example above, in the ReceiveString receiver method, it would seem that we would need to do the assignment by using DeepClone(), i.e. this.lastStringInput = input.DeepClone();. The reason this is not necessary is because strings in C# are immutable and the simple assignment operator creates a new string object. In general though, for reference types, DeepClone would need to be used to retain the value past the lifetime of the receiver method.

Finally, with respect to output streams, it is important to note that a component can post a value to the output stream (via a Post call) and is free to immediately change the value. All the receivers that are connected to this emitter will receive the value that was provided during the call to Post. This is again accomplished by the runtime via automated cloning.

The Shared Objects in-depth topic contains more information about message cloning.

We have so far discussed how to write a general \psi component, i.e. one with any number of input and output streams. We have also discussed how components are scheduled for execution by the runtime and how data is passed to them. We now turn attention to stream operators, or consumer-producer components, which are a particular case of the more general component presented above. Specifically, they are components that have a single input and a single output.

Since writing single-input / single-output components that process a stream is a common task, the \psi framework provides a base class, i.e. ConsumerProducer<TIn, TOut> that can be used to simplify the construction of these components. Below is an example consumer-producer component that computes the sign (+1 or -1) of a stream of doubles.

// The class defines a consumer-producer component

public class Sign : ConsumerProducer<double, int>

{

// Constructor

public Sign(Pipeline p)

: base(p) { }

// Override receiver method

protected override void Receive(double data, Envelope envelope)

{

this.Out.Post(Math.Sign(data), envelope.OriginatingTime);

}

}The constructor for the base class ConsumerProducer builds the receiver In of type double and the emitter Out of type int and provide a virtual receiver method which the developer can override. In the receiver method, we compute and post the result to the Out emitter.

We have seen in the previous section that components can be used in an application by instantiating them and connecting them to other streams via the PipeTo operator. In the case of simple consumer-producer components, a simple design pattern enables the construction of stream operators and simplifies usage in the application. The pattern involves creating an extension method for the streams of type double that wraps the component creation and connection steps, like below:

// static class for defining stream operator extension methods

public static class Operators

{

// static stream operator method

public static IProducer<int> Sign(this IProducer<double> source, DeliveryPolicy<double> deliveryPolicy = null)

{

// create the component

var signComponent = new Sign(source.Out.Pipeline);

// pipe the source stream to it

source.PipeTo(signComponent, deliveryPolicy);

// return the output

return signComponent.Out;

}

}The extension methods extends IProducer<double>, which represents a stream of double. Inside, it instantiates a new component (note that we can get a hold of the pipeline required to construct the component from the source stream), and connects the source stream to it, and returns the result. Notice how the stream operator also takes a deliveryPolicy parameter, with a default null value and uses it when connecting the source stream to the underlying component. This deliveryPolicy enables developers to control how messages are delivered to the component when computational constraints prevent the component from being able to process all messages at the rate at which they arrive. The Delivery Policies tutorial contains more information about how delivery policies operate.

The constructed stream operator Sign() now becomes available on any stream of doubles, for instance, we can now write:

var stream = Generators.Sequence(p, 1.0, x => x + 1, 10);

stream.Sign().Do(s => Console.WriteLine($"Sign: {s}"));The Basic Stream Operators in the \psi runtime, like Select, Do, Where, etc., are implemented using this pattern.

A final note regarding a few interfaces that are available, IConsumerProducer<TIn, TOut>, IConsumer<TIn> and IProducer<TOut>. If you take a look at the ConsumerProducer class (under Sources\Runtime\Microsoft.Psi\Components\ConsumerProducer.cs), you will notice that it implements the IConsumerProducer<TIn, TOut> interface, which is an aggregate of the IConsumer<TIn> and IProducer<TOut> interfaces. These interfaces merely specify that a class has an In receiver, and/or an Out emitter. They are used largely for creating syntactic convenience. Specifically, they enable the PipeTo operator to take as an argument the component class directly, rather than the corresponding receiver. For instance, in the example above, we were able to say directly

source.PipeTo(signComponent, deliveryPolicy);instead of

source.PipeTo(signComponent.In, deliveryPolicy)because the Sign component implements IConsumer and PipeTo knows how to route to an IConsumer. By deriving from ConsumerProducer<TIn, TOut> your component class automatically implements this interface.

Subpipelines are a construct that enable hierarchical organization in the computation graph. They enable developing composite components, or dynamic computation graphs that can have a lifetime separate from their parent Pipeline.

The Subpipeline class is essentially a Pipeline (it derives from it), but is also a component that can be added to a parent pipeline. This allows for a means of abstraction and for hierarchically organizing computation graphs via composite components, which we describe in more detail in the next section. Additionally, subpipelines may have a lifetime that is independent of that of their parent. Finally, subpipelines enable initializing and starting or stopping child components independently from the parent to which they belong, and hence dynamically constructing computation graphs. As an example, subpipelines are used internally by the Parallel operator to dynamically create and run parallel computation graphs for multiple instances, while respecting source component initialization, start and stop events, etc.

Because they may include source components, subpipelines implement the ISourceComponent interface and complete when all of their child source components have completed. If a Subpipeline contains no source components then it completes (calls notifyCompletionTime) at startup, and therefore behaves as a purely reactive component.

Subpipelines have their own Scheduler, and unless otherwise specified, adopt a DeliveryPolicy.Unlimited default delivery policy.

If not explicitly started via Run() or RunAsync(), subpipelines start when the parent pipeline starts - just as a normal component. They may also be created and started dynamically at runtime.

Constructing a subpipeline and attaching components to it is simple:

using (var p = Pipeline.Create("root"))

{

using (var s = Subpipeline.Create(p, "sub"))

{

// add to sub-pipeline

var seq = Generators.Sequence(s, new[] { 1, 2, 3 });

p.Run(); // run parent pipeline

}

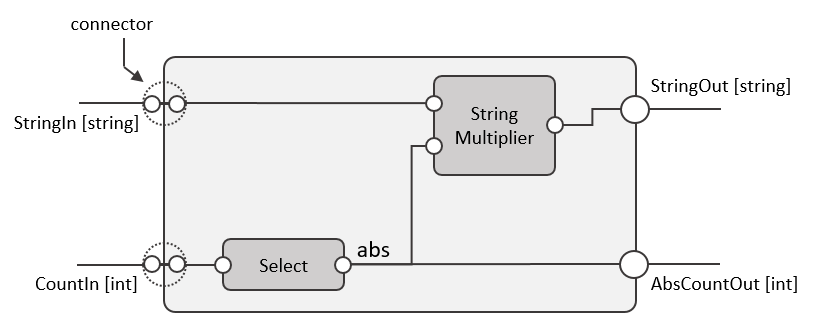

}Composite-components allow for aggregating a graph of existing components in a single, higher-level component. As an example, consider the figure below. The composite-component depicted here wraps the previous StringMultiplier component, together with a stream operator component that computes the absolute value of the input stream into a single composite-component with two inputs and two outputs. The inputs correspond like before to a string and count. On the output side, will provide the multiplied string and absolute value of the count. Like in the previous example, this composite-component is not very useful, but will help illustrate how composite-components are created.

The code for this composite-component is shown below:

// Implements a simple composite-component

public class CompositeComponent : Subpipeline

{

// Connector for the string input

private Connector<string> stringIn;

// Connector for the count input

private Connector<int> countIn;

// Constructor

public CompositeComponent(Pipeline pipeline)

: base(pipeline, nameof(CompositeComponent))

{

// Create the connectors

this.stringIn = this.CreateInputConnectorFrom<string>(pipeline, nameof(this.StringIn));

this.countIn = this.CreateInputConnectorFrom<int>(pipeline, nameof(this.CountIn));

// Define the outputs

var stringOut = this.CreateOutputConnectorTo<string>(pipeline, nameof(this.StringOut));

var absCountOut = this.CreateOutputConnectorTo<int>(pipeline, nameof(this.AbsCountOut));

this.StringOut = stringOut.Out;

this.AbsCountOut = absCountOut.Out;

// Create the string multiplier component, and connect it

var stringMultiplierComponent = new StringMultiplier(this);

this.stringIn.Out.PipeTo(stringMultiplierComponent.StringIn);

stringMultiplierComponent.Out.PipeTo(stringOut);

// Create the absolute value of count stream by applying a Select operator

var abs = this.countIn.Out.Select(v => v > 0 ? v : -v);

abs.PipeTo(stringMultiplierComponent.CountIn);

abs.Out.PipeTo(absCountOut);

}

// Receiver for string input

public Receiver<string> StringIn => this.stringIn.In;

// Receiver for count input

public Receiver<int> CountIn => this.countIn.In;

// Emitter for string output

public Emitter<string> StringOut { get; private set; }

// Emitter for absolute count output

public Emitter<int> AbsCountOut { get; private set; }

}Like with a regular component, a composite-component is written as a class. A recommended approach is to inherit from Subpipeline; providing a clear delineation in the graph (future tools may collapse graph visualization, for example). The constructor also receives the pipeline object, and sets up the receivers and emitters. The difference is in that there are no receiver methods. Instead, receivers for composite-components can be setup with the help of connectors, implemented by the Connector<T> class. A connector exposes a member In that acts as a receiver, and a member Out that acts as an emitter. This way, it can live on the input boundary of the composite-component and be seen as a receiver from outside the component and as an emitter from inside. The constructor code can then create a number of sub-components and wire them together to the connector outputs. Also notice that internal components are given the subpipeline as their host upon construction (e.g. new StringMultiplier(this)). This ensures that the inner components remain isolated from the parent pipeline while also not exposing subpipeline emitters to the outside world. Example:

this.stringIn.Out.PipeTo(stringMultiplierComponent.StringIn);On the output side, the composite-component emitters can be assigned directly from the sub-component emitter or existing wiring — see the last couple of lines in the constructor above.

Applications or components may need to do setup and teardown work just before the pipeline runs and/or after it completes. For this, the Pipeline provides events which may be subscribed to and handled as appropriate:

// Event that is raised when the pipeline starts running.

event EventHandler<PipelineRunEventArgs> PipelineRun;

// Event that is raised upon pipeline completion.

event EventHandler<PipelineCompletedEventArgs> PipelineCompleted;The PipelineRun event is raised when the pipeline starts running, but before any messages begin to flow. The PipelineCompleted is raised upon pipeline completion, when all components have been stopped and messages are no longer being produced. As the pipeline is not in a running state, no messages should be posted in the handlers for either of these events.

In contrast to reactive components, which are those that produce output only in response to incoming message, source components are the "headwaters" of the system; the source from which messages flow. These are components that originate streams of data. Typically these components encapsulate sensors, such as cameras, microphones, accelerometers, etc., but may also represent hybrid components which both react to, as well as produce, streams of data.

Source components must be declared as such for the pipeline to behave correctly. The ISourceComponent interface serves this purpose.

Some source components have a notion of "completion". These represent finite streams of data. These are commonly "importers" of some kind; producing messages from a data source. The data is finite and so is the source component. The Start(Action<DateTime> notifyCompletionTime) method provides a means for the component to later notify the pipeline of completion by way of a notifyCompletionTime action to call once no more messages are forthcoming and indicating the originating time of the final message (or else pipeline.GetCurrentTime()). Source components that are truly infinite and do not have a notion of completion (e.g. an always-on camera or other sensor component) should invoke the notifyCompletionTime action with a time of DateTime.MaxValue.

// Implementors should advise the pipeline when they are done posting as well as

// the originating time of completion; on or after the final message originating time

void ISourceComponent.Start(Action<DateTime> notifyCompletionTime);Start(...) is called during pipeline startup, after the graph of components has been constructed. Once a source component's Start() method has been called, it may begin posting messages at any point thereafter. Component receivers need to handle the possibilty of receiving and reacting to messages during startup.

Once all source components have completed, downstream reactive components no longer have anything to which to react and the pipeline is free to shut down. Any cycles in the graph where reactive components are "down stream" from themselves do not prevent pipeline shut down.

// Called by the pipeline when shutting down.

void ISourceComponent.Stop(DateTime finalOriginatingTime, Action notifyCompleted);Stop(...) is called to notify the source component that the pipeline is shutting down. The finalOriginatingTime indicates the pipeline time after which no messages bearing a later originating time will be delivered. However, if a source component expects to produce but has yet to post messages with originating times before finalOriginatingTime, then it should continue to generate and post such messages. As soon as it has done so, or as soon as it can guarantee that it will never post any more messages with an originating time less than or equal to finalOriginatingTime, it should invoke the notifyCompleted action to inform the pipeline that it has completed generating source messages. However, if the component does have inputs, it is expected to continue to handle incoming messages, which may include posting messages from inside its receivers.

Some source components are "infinite sources". They produce perpetual streams of data which do not have a notion of completion, such as an "always-on" sensor. Such components should implement ISourceComponent and call notifyCompletionTime(DateTime.MaxValue) in their Start(Action<DateTime> notifyCompletionTime) method. The DateTime.MaxValue as the final originating time tells the runtime to expect an infinite stream from the component.

In the discussion above, we have assumed that the source component obtains data via a thread that it starts or obtains, but that cannot be controlled by the runtime scheduler. However, this also means that the runtime cannot throttle these components, i.e. it cannot slow down the production of the source messages if it needs to (for instance if resource constraints prevent the full pipeline to run at the speed of the source).

To permit this type of dynamic slow down of data sources, the runtime offers a generator pattern that enables writing source components that can by under the control of the scheduler. A base, abstract component class called Generator is provided. The example below, which can be found in the Test.Psi project under Sources\Runtime\Test.Psi\GeneratorSample.cs illustrates how to write such a generator class that reads in a text file with two columns and outputs two streams, each containing the data corresponding to each column.

using System;

using System.IO;

using Microsoft.Psi;

using Microsoft.Psi.Components;

// This example loads a text file and outputs each line

// a line is expected to contain a timestamp and a value, which can be either an int or a string

// e.g.:

// 1000, 10

// 2000, this is a test

// 3000, of multi-stream generator

// 4000, 11

public class GeneratorSample : Generator

{

private TextReader reader;

public GeneratorSample(Pipeline p, string fileName)

: base(p)

{

this.OutInt = p.CreateEmitter<int>(this, nameof(this.OutInt));

this.OutString = p.CreateEmitter<string>(this, nameof(this.OutString));

this.reader = File.OpenText(fileName);

}

public Emitter<int> OutInt { get; }

public Emitter<string> OutString { get; }

// read the file line by line,

// and post either an int value or a string value to the appropriate output stream

protected override DateTime GenerateNext(DateTime previous)

{

string line = this.reader.ReadLine();

if (line == null)

{

return DateTime.MaxValue; // no more data

}

// first value in each line is the timestamp (ticks),

// second is either an int or a string, separated by ','

var parts = line.Split(new[] { ',' }, 2);

// parse the originating time.

// If the data doesn't come with a timestamp, pipeline.GetCurrentTime() can be used instead

var originatingTime = DateTime.Parse(parts[0].Trim());

if (int.TryParse(parts[1].Trim(), out int intValue))

{

this.OutInt.Post(intValue, originatingTime);

}

else

{

this.OutString.Post(parts[1], originatingTime);

}

return originatingTime;

}

}The component must override the virtual GenerateNext method to produce data on the output streams (in this case OutInt and OutString. This method will be called to produce data when the runtime decides the pipeline is ready to consume it. The method must return the originating time of the last message it posted. Internally, the base Generator class has a loopback mechanism where a message with the originating time equal to the return value of the GenerateNext method is posted back to a (hidden) input of the component. The GenerateNext method is called from the receiver method for this loop-back input (for details, see Sources\Runtime\Microsoft.Psi\Components\Generator.cs. This way, because this loop-back message is being scheduled like any other message in the pipeline, the runtime can control when the next data is generated. The pace at which data is produced is in this case under the scheduler control.

In general, follow the guidelines we have already provided above when writing components.

If you are writing a single-input, single-output component, use the ConsumerProducer<TIn, TOut> base class and write a corresponding stream operator as an extension method as this will simplify authoring. Make sure the stream operator takes a DeliveryPolicy<TIn> parameter, and uses it when creating the connection to the receiver of the consumer-producer class.

If your component has a single input, but multiple outputs, name the input In and implement the IConsumer<T> interface. Similarly, if your component has multiple inputs but a single output, name the output Out and implement the IProducer<T> interface.

If your component posts messages from outside its receiver(s) that are not generated in response to messages received (e.g. from its own threads or event handlers), then it is a source component and should implement the ISourceComponent interface. Such messages must not be posted before the interface's Start method is called or after the Stop method returns. However, purely reactive messages (i.e. those that are produced in response to a received message) may continue to be posted from within a receiver method.

If your component has multiple inputs and multiple outputs, we recommend you name the inputs using a pattern FooIn, e.g. AudioIn, ImageIn, etc. and the outputs using the pattern FooOut, e.g. AudioOut, ImageOut, etc. This way, developers can use the auto-completion features in Intellisense to quickly discover the inputs and outputs a component might have by just typing "In" or "Out" after component and ".".

If your component uses unmanaged resources, also implement IDisposable. The \psi runtime will call the Dispose() method on all components when the pipeline shuts down, allowing the to free unmanaged resources.

- Basic Stream Operators

- Writing Components

- Pipeline Execution

- Delivery Policies

- Stream Fusion and Merging

- Interpolation and Sampling

- Windowing Operators

- Stream Generators

- Parallel Operator

- Intervals

- Data Visualization (PsiStudio)

- Data Annotation (PsiStudio)

- Distributed Systems

- Bridging to Other Ecosystems

- Debugging and Diagnostics

- Shared Objects

- Datasets

- Event Sources

- 3rd Party Visualizers

- 3rd Party Stream Readers

Components and Toolkits

- List of NuGet Packages

- List of Components

- Audio Overview

- Azure Kinect Overview

- Kinect Overview

- Speech and Language Overview

- Imaging Overview

- Media Overview

- ONNX Overview

- Finite State Machine Toolkit

- Mixed Reality Overview

- How to Build/Configure

- How to Define Tasks

- How to Place Holograms

- Data Types Collected

- System Transparency Note

Community

Project Management