You may also enjoy another online prover that produces tableaux

Famous logician Raymond Smullyan used a proof procedure called analytic tableaux to prove tautologies in propositional logic.

This program is based on chapters from three books by Smullyan:

- A Beginner's Guide to Mathematical Logic, Dover, 2014, chapter 6

- Logical Labyrinths, CRC Press, 2009, chapter 11

- First Order Logic, Dover, 1995, chapter II

All three books have essentially the same explanation with slight variations. This project does signed tableaux. I'm amused by this method of proof. During the proof, you never assign a valuation to the propositional identifers. Making inferences is based solely on syntax and sign of a formula. It almost seems magical.

The golang program tableaux supports these binary infix logical oparators:

&- conjunction|- disjunction>- material implication=- logical equivalence

And one unary prefix operator, ~, for negation.

The parser does apply operator precedence: e = d > c | b & ~a ends up fully parenthesized like this:

e = (d > (c | (b & ~a))). The precedence is: ~ → & → | → > → =. Negation symbol binds

tighter than Conjuction symbol, and so forth.

Expressing logical equivalence without the = operator would look like this:

(a > b) & (b > a)

In this case, parentheses need to exist. The expression a > b & b > a gets parsed as (a > (b & b)) > a

$ make tableaux

You invoke tableaux with one or more expressions on the command line. A single expression

causes tableaux to use that expression in a proof of tautology. More than one expression

causes tableaux to treat the all but the last expression as hypotheses, then check that

the final expression is or is not a logical consequence of the hypotheses.

tableaux produces a text representation of the final tableau on stdout. You can invoke it

with a -g _filename_ argument, which will write GraphViz dot input format to the file named.

The makefile for this project creates the parse tree and finished tableau dot inputs for

the images below: make diagrams will re-create them.

Invoked with a single propositional logic expression, tableaux

writes out a tableau that proves whether the expression constitutes

a tautology or not.

$ ./tableaux '((p>q)>r) > ((p>q)>(p>r))'

Expression: "((p > q) > r) > ((p > q) > (p > r))"

/*

0. false: ((p > q) > r) > ((p > q) > (p > r))

1. true: (p > q) > r (0)

2. false: (p > q) > (p > r) (0)

3 left, 4 right

3. false: p > q (1)

5. true: p > q (2) contradicts 3

4. true: r (1)

6. true: p > q (2)

7. false: p > r (2)

8 left, 9 right

8. false: p (6)

10. true: p (7) contradicts 8

9. true: q (6)

11. true: p (7)

12. false: r (7) contradicts 4

Formula is a tautology

*/

Line 0 holds the expression to be proved a tautology signed false. Lines 1 and 2 are inferences of line 0, marked "(0)". Sunjoined inteferences of line 1 cause a branch, line 3 on the left, line 4 on the right. Lines 3 and 4 are marked "(1)". Leaf nodes that close a branch have the line they contradict. Line 10 closes a branch, it's an inference of line 7 and it contradicts line 8.

Called with more than one propositional logic expression, tableaux proves

whether or not the final expression is a logical consequence of the other expressions.

The following checks whether x > ~y is a logical conseqeunce

of (x & y) > z and (x & y) > ~z

You might see this written in a book as: (x ∧ y) ⊃ z, (x ∧ y) ⊃ ∼z ⊦ x ⊃ ∼y

$ ./tableaux '(x&y)>z' '(x&y)>~z' 'x>~y'

Hypothesis: "(x & y) > z"

Hypothesis: "(x & y) > ~z"

Consequence: "x > ~y"

/*

0. true: (x & y) > z

1. true: (x & y) > ~z

2. false: x > ~y

3 left, 4 right

3. false: x & y (0)

5 left, 6 right

...

21. false: x (5) contradicts 9

22. false: y (5)

23. true: y (10) contradicts 22

x > ~y is a logical consequence of hypotheses

*/

As pseudocode:

do {

find all unclosed leaf nodes of tableau

if no unclosed leave nodes exist {

the expression is tautological

exit the do-loop

}

for each unclosed leaf node {

Find an unused forumla as far up the tableau as possible

on the branch that the unclosed leaf node resides on.

if such an unused formula exits {

Subjoin inferences of the unused formula to all

unclosed leaf nodes beneath it in the tableau.

Mark inferences that consist of a signed identifer as used.

Check each newly-subjoined inference for contradictions with

previous inferences in the tableau's branch it resides on. Mark

any leaf nodes that cause a contradiction as closed.

Mark the unused formula as used.

exit for-each loop over unclosed leaf nodes. The list of unclosed

leaf nodes is invalid, as new leaves have been subjoined.

} else {

the do loop should terminate

}

}

} while an unused formula was found

This algorithm terminates when no unused formulas exist in the tableau, or no unclosed branches exist. If no unclosed branches exist, the original input formula is a tautology, otherwise, it is not.

The algorithm is guaranteed to terminate. Each subjoined formula, the result of making 1 or 2 inferences from a previously unused formula, has one logical operator (&, |, >, =, ~) fewer than the expression inferred from. Eventually, the result of every inference will be a identifier without any operators. When every formula in the tableau has had its inferences subjoined (all the formulas are used), the tableau is complete. The algorithm above may terminate before the tableau is fully populated, by finding contradictions in branch(es) before every formula is used.

You can get an upper bound on the maximum branch depth of a tableau by counting all operators in the original expression:

- Negation counts for 1

- Equivalence, implication, conjunction, disjunction count for 2

The depth of the longest branch will be no greater than what you count.

See README for package parser for details about internals.

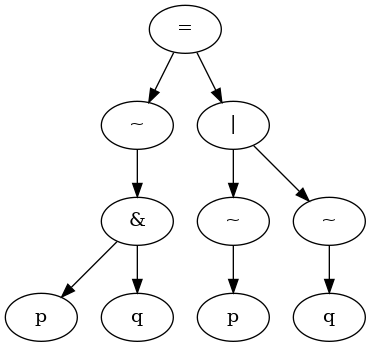

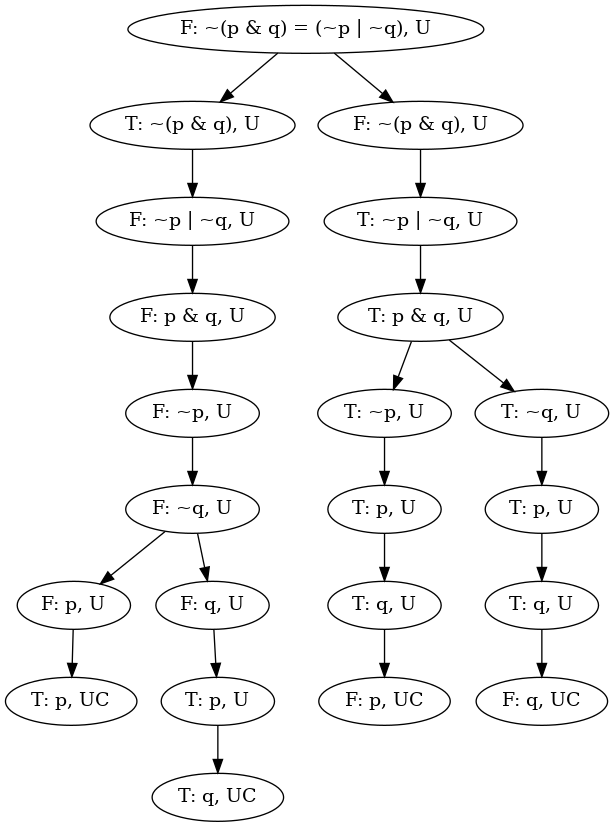

Note that a parse tree constructed by packages lexer and parser differs

from a (finished) tableau.

Parse tree for ~(p&q)=(~p|~q)

Finished tableau for ~(p&q)=(~p|~q)

Incautious reading any of the 3 Smullyan books above would have you

believe that an analytic tableau consists of arrays of subexpressions of the propositional

logic formula to be proved. Smullyan was not a programmer, it seems, because a tableau is

a binary tree of individual subexpressions. The sign part of an analytic tableau is attached

to a subexpression, as is the notion of an unused formula, and whether a branch is closed or not.

A finished tableau tree isn't a complete tree, doesn't have heap structure, and a lot of the

interior nodes only have one child. I used the Left element of a Tnode for the child of

those interior nodes with only one child.

type Tnode struct {

LineNumber int

Contradictory *Tnode

inferredFrom *Tnode

Sign bool

Tree *node.Node

Expression string

Parent *Tnode

Left *Tnode

Right *Tnode

Used bool

closed bool

}

The Sign and Expression members of this struct identify a node in a tableau. Apparent duplicate

nodes can appear in a tableau, because the logic-not handling for a program is more literal than

for a human. Because the proof procedure checks for contractions with previous subexpressions in

a tableau branch, a node has to have a link back to its "parent" in the tableau. Only the root

node of a tableau's binary tree has a nil value for Parent. Each node in a tableau keeps a pointer

to the node of a parse tree that corresponds to the tableau node itself. Subjoining inferences

to leaf nodes of a branch uses the principal connective of its parse tree pointer to decide

how to subjoin (linearly or bifurcate), and the sign of the subjoined expressions.

Haing the type of Tnode.Sign as a Golang boolean is semantically obvious: the signs of expressions

in Smullyan's tableaux are 'T' or 'F', but internally, a program could use 0 and 1, or even

two different strings. Checking two lines in a tableau (two nodes in a binary tree) for

contradiction only involves non-equality of the Sign element, and string equality of the

Expression element. A program could check the Tree elements for tree-equality, but since

the tableaux.Print() method canonicalizes string representations of tableau binary trees, string equality

is sufficient.

I started with a Golang parser for propositional logic expressions, v2.0 . The idea was to edge up to a tableaux method tautology prover.

- Write lexer for propositional logic tokens

- Write propositional logic parser

- Write truth table generator based on the parser

- Write single-level tableaux generator

- Write full-on tableaux prover

./truthtable '(p&q>...)'

Prints a truth table for the command line expression. The expression gets parsed and

evaluated with every combination of true and false for each variable. Can be helpful

verifying whether tableaux gets its proof correct.

./tokentest 'a&b&c())~|>='

Runs the lexer over the command line argument, and prints out all the tokens it finds,

and their types. Used to write and debug package lexer

./recognizer test_input/001

Uses a simpler recursive descent grammar than tableaux does to recognize propositional logic

formula. Used to learn how to write a recursive descent grammar in Go.

./parsetest test_input/004

Lexes, parses, then prints the propositional logic expressions in the file named

on command line. Used to develop and debug package parser