by Sam Halperin

This discussion covers research on recent computer graphics pedagogy, with a particular eye towards major themes and implementation level technologies. For example, one theme that recurs throughout the research is the need to strike a balance between engaging beginning students to continue studying computer science, and the need to provide a foundation rooted in rigorous data structures and algorithms. A second theme that recurs is the need to abstract away the complexity of systems intended for engineering (Android SDK, OpenGL), in order to use them for teaching purposes. Presented as well, are case studies from the literature that implement these and other themes.

The paper concludes with some reflections on visual media as a tool for learning programming and a section on future research, as well as an appendix that briefly tries to tie some of the themes here to actual code in JavaScript.

Keywords—computer graphics; computer art; pedagogy

To teach computer graphics as a context for learning computer science means to use computer graphics to keep students engaged as they learn foundational skills. One of the themes that comes up recurrently in research on introductory level teaching is that of using a context such as mobile applications or graphics for making CS interesting to beginner students. (Ilinkin 2014; Bayzick, Kalufut, & Spear, 2013; Greenberg, Kumar & Xu 2012) Here the goal seems less to produce experts in a particular technology stack then to spark a creative flame around the expressiveness of code.

There are varying levels of this approach used in the research: Some research has students implementing functionality in a toy graphics language, drawing simple shapes and making simple, throw-away games (Ilinkin 2014). On the other hand, some projects focus on design and technology skills applied to high level graphics engines in order to create for-public-consumption, finished projects (Romero et al., 2014).

The rationale for the focus on context, rather than functions, data structures, and algorithms, without context, is the need to engage ‘wired’ students (Greenberg et al., 2012). This refers to a desensitization of students to the impact of visual electronic media. Creating “passion” for programming, through tangible results, in this respect is critical (Bazyick et al., 2013).

Open for discussion is whether imbuing introductory classes with context tips the scales away from academic rigor in these classes. Bayzick et al. note, in a discussion of programming competitions using their teaching library ALE: “ALE can serve as the foundation for campus-wide programming competitions. Since the barrier to entry is low and since the need for rich media often trumps the quality of the source code, it is possible that non-majors and new majors can “win” despite the greater programming experience of more senior competitors.” (2013)

It seems that pursuing rigor in software engineering is a lifelong activity based in constant professional development, and that a path into computer science and software engineering should exist for the college freshman (and indeed the adult student), regardless of previous math/programming background. But also that programming competitions should be won by role models in programming not by “developers” of the best art and design assets.

The challenge with creating exercises that appeal to ‘wired’ students is that programming for interactivity and animation often requires management of asynchronous, called-back, event-driven, and sometimes multi-threaded code. Often the goal of abstractions created for pedagogical purposes on top of more complex systems is to create a linear, straight-line, programming system out of a more complex one (Bayzik et al., 2013, Necaise 2014).

It is clear from limited experience teaching beginners, and supported by literature (Bayzick et al, 2013) that the concepts that don’t make clear a cause and effect apparent (decorators are a good example of this in Python, as are success/error callbacks to an AJAX function in JavaScript), are more confusing to beginners than others. Many of the reviews studied use simplification as a rationale for their ‘toy’, teaching abstractions (Necaise, 2014; Greenberg et al., 2012; Ilinkin 2014) over some other motivation like presenting code of better quality (as in Bayzick et al., 2013).

While the abstractions necessitated by “straightforward, sequential” (Illinkin 2014) programming modes above impose restrictions on the choice of technical frameworks and libraries, it is clear that there is also a demand for commercially and culturally relevant tools. The studies that used Android as an ecosystem both lauded the capacity of even beginner programmers to produce Android applications, and pointed to the relevance of the environment as a motivator. (Bayzick et al., 2013; Illinkin 2014).

Whether these projects can, given the level of sophistication of their architects, represent authentic and valuable entry into the relevant marketplaces (Play store for Android, App store for iOS) remains to be seen. The public presentation of finished projects themselves, and the publicity that they generate has been cited as a good student motivator (Romero et al, 2014), so perhaps commercial success within the app-stores is not critical.

“Programming is not the only job skill” (Bayzick et al., 2013). Arguably a primary consideration for introductory programming is teaching programming and creating good software engineering colleagues out of students.

“Head down” work constitutes the core of modern software engineering, but for the time-in-IDE (or terminal) to contribute to the forward movement of a project, it has to be supported by many non-programming tasks. Among these, current research cites the following as important: integrating multiple international viewpoints in terms of language and culture outside of the classroom, lab, or office (Achuthan, Ramesh, Punnekkat, Raman, 2014); the way in which technical expressions of mathematics and logic can help bridge these international divisions (Yang, 2014); participation with non-technical (ie. design/art/business oriented) peers on an equal footing centered on mutual respect and mutual reliance (Romero et al., 2014); The importance of inclusion, by focusing on non-gendered, non-violent, socially conscious media, particularly as it affects the participation of demographics that are typically underrepresented in computer science (Bayzick et al., 2013). This last issue is called out specifically in the case study below.

Computer Assisted Instruction is emerging as a theme in teaching technical subjects like Math (Yang, 2014). Yang suggests that automated evaluation is one of the tools that could be used to scale up science education, and argues courseware, rather than the teacher figure, should “dominate” the educational experience. Certainly there is a tradition in machine verified grading in computer science. However, experience with automatically evaluated schemes for grading graphics assignments have been unsatisfying, with grading bugs emerging around screen pixel density and browser zoom level during one MOOC graphics class. Perhaps this could be an area for future research.

In terms of the fast moving commercial ecosystem it is relevant to consider portability in terms not only of technologies, but of techniques. Bayzick proposes a standard for good pedagogical artifacts that centers around well documented, clean source code (Bayzick et.al., 2013). This is a hopeful standard over something like idiomatic use of languages and libraries, in that writing good code is largely a portable skillset. Idiomatic use of a language, on the other hand, is highly dependent on full-time engagement with a particular language, API, or technology, and in-person interaction with its practitioners.

The focus of recent pedagogy also overwhelmingly reflects a transition away from algorithms and bare metal implementation, to integration and application development. This represents a focus on en-vogue technology, rather than bare-metal computer science. This magnifies the resource requirements of becoming expert in, and teaching a diverse array of high level toolkits.

Blank pointed at a key issue in systems for teaching beginner computer science, namely the phenomenon that as a beginner, one is tied closely to the first language used (Blank, Kay, Marshall, O’Hara, Russo, 2012). While this theme does not recur in other writing reviewed, it seems important to carefully consider not only the relevance (within the current technological zeitgeist) of a first language, but also its suitability as a foundation for informing future studies. One might ask the question whether learning a compiled language with strong typing and a C-like syntax is a better foundation than learning a forgiving interpreted language. (eg: Learning Java informs JavaScript, C, C++, Perl, and Python development, and is relevant with respect to the large deployed base of Android devices, but is unforgiving in terms of the type system. On the other hand Perl and Python are forgiving, might inform other dynamic languages like JavaScript, but – particularly in the case of Perl, are no longer relevant with respect to the technological zeitgeist, and don’t inform programming in a statically typed, compiled language.)

In the case study by Bayzick et. al., the emphasis is on learning good coding practice by reading high quality, well documented code. This stems from teaching to the ‘nothing from scratch’ philosophy that they identify.

To implement the courseware here, the team built an extension to a lower level Android graphics library, and in doing so created a starter codebase on which students could build their features. It is worth noting that the abstraction was built on AndEngine a 2D Android Game Engine, so the courseware represents a very high level abstraction built on an already moderately high one (as opposed to say on OpenGL).

The question that is worth studying is, does this approach – building on an ultra-high level abstraction on top of Android – afford the opportunity to get future, more meaningful experience with lower level development, either through the knowledge imparted, or through entry-level employment based on a portfolio of real work. (Even if that portfolio doesn’t reflect a meaningful interaction with data structures, algorithms, functional programming, object orientation…etc.) Or, does it constrain the developer to continually interact with high level implementations?

The most significant innovation in Bayzick et al., however is not technical, but cultural: namely the strict focus on non-gendered and non-violent game artifacts built along a social mission. The authors noted significantly, that this approach produced a more diverse cross section of successful course completers in terms of not only gender, but presumably technology orientation. (With the assumption that a person’s preference for violent, misogynistic video games does not imply an aptitude for computer science.)

In the study by Romero et. al., (2014) there is a clear emphasis on both publishing projects, as well as on the teamwork needed between developers and designers to launch a project into the public sphere.

It is interesting to note that this emphasis on public performance and the development of successful, impactful artifacts (as evidenced by the valuing of press about a project in a local newspaper) isn’t necessarily held across geographic boundaries. In a more traditional evaluation of pedagogy by Wei & Du, (2013) there is a focus on more traditional evaluation of the ‘weight’ of student’s source code in terms of Source Lines of Code and Lines of Code.

LOC metrics are the source of a long standing argument in the software engineering community, and with other metrics like cyclomatic complexity, forming a desire to quantify the amount of effort and technical expertise that a project represents. This is relevant in the current marketplace, with indicators of these metrics; commit quantity, lines committed, issues closed…etc., used as hiring criteria on the central source code sharing site GitHub.

My critique of Romero’s study, in some sense echoing the sentiments of Wei & Du (2013): Though not applied specifically to Romero’s work, their sentiment applied to this case study is that the emphasis on public performance at once emphasizes wrapped, closed, complete projects, but neglects to inform us about the technical integrity of the knowledge gained in the process (ie through LOC). At some point though one must acknowledge that this trade off is probably very appropriate to a class at this level, and might create, through early satisfying visual results, a passionate commitment to going back and learning the low level math and science at a later point.

While the emphasis in Romero’s study is on public performance, the emphasis in a study done by Shesh (2013) is on low-level insights into the workings of components in a computer graphics application. For example, Shesh’s students gain first-person insights into n-ary trees and their traversal by implementing a scene graph and ray-tracing engine. Shesh acknowledges, as did the previous studies, that enrollment and engagement are important factors in structuring a computer graphics course at this level, but seems to make the tradeoff between rigor and satisfaction in favor of rigor. Shesh notes that in order to provide students with low-level experience of data structures in graphics, it was necessary to provide significant completed code to students. This theme is taken up briefly in the appendix.

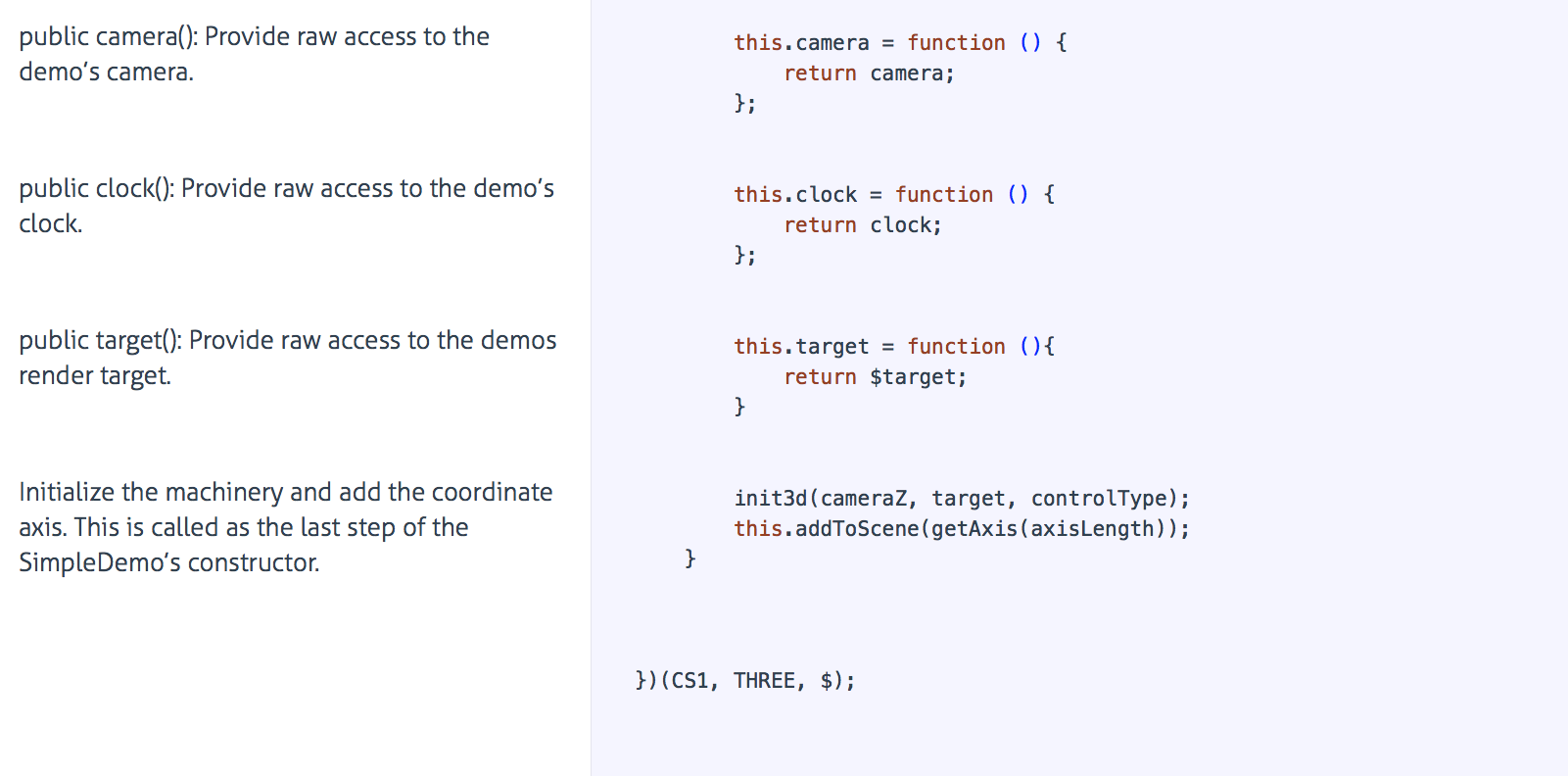

The challenge in bringing computer graphics as a context for learning programming to adult learners in particular, as in a typical front-end development course, is that students have no background in programming, graphics, or linear algebra. A relevant question would be how to ‘bootstrap’ learning so that students could start creating lines, solids, polygons, immediately, and build on simple graphics as a way to understand looping, logic, algorithms…etc. (See appendix 1 for a creative, first start at simplifying a language like THREE.js to be suitable in this role.

There is also a certain class of students for whom visual media is a very strong way, perhaps the only way, to get an early handle on more abstract concepts like functions, objects, and loops. With a visual toehold on basic data structures, branching, and looping constructs, they then succeed in more traditional advanced studies

For an implementation-level example: sorting, a typical first year CS topic, can be understood through looking at textual ordered data, as well as by seeing (or more importantly implementing) a speckled, random set of cells in an array or matrix, turn into a smooth gradient after sorting based on value or hue. Visual feedback on algorithm development can enable comprehension of progressively more complicated routines (Maeda 2001).

Within the context of a front-end development course, or even an introductory programming course focused on back-end development, a short module that ties in computer graphics could be a valuable add-on. It might serve to reach the visually oriented students described above, or speak better to interdisciplinary students without a formal math background.

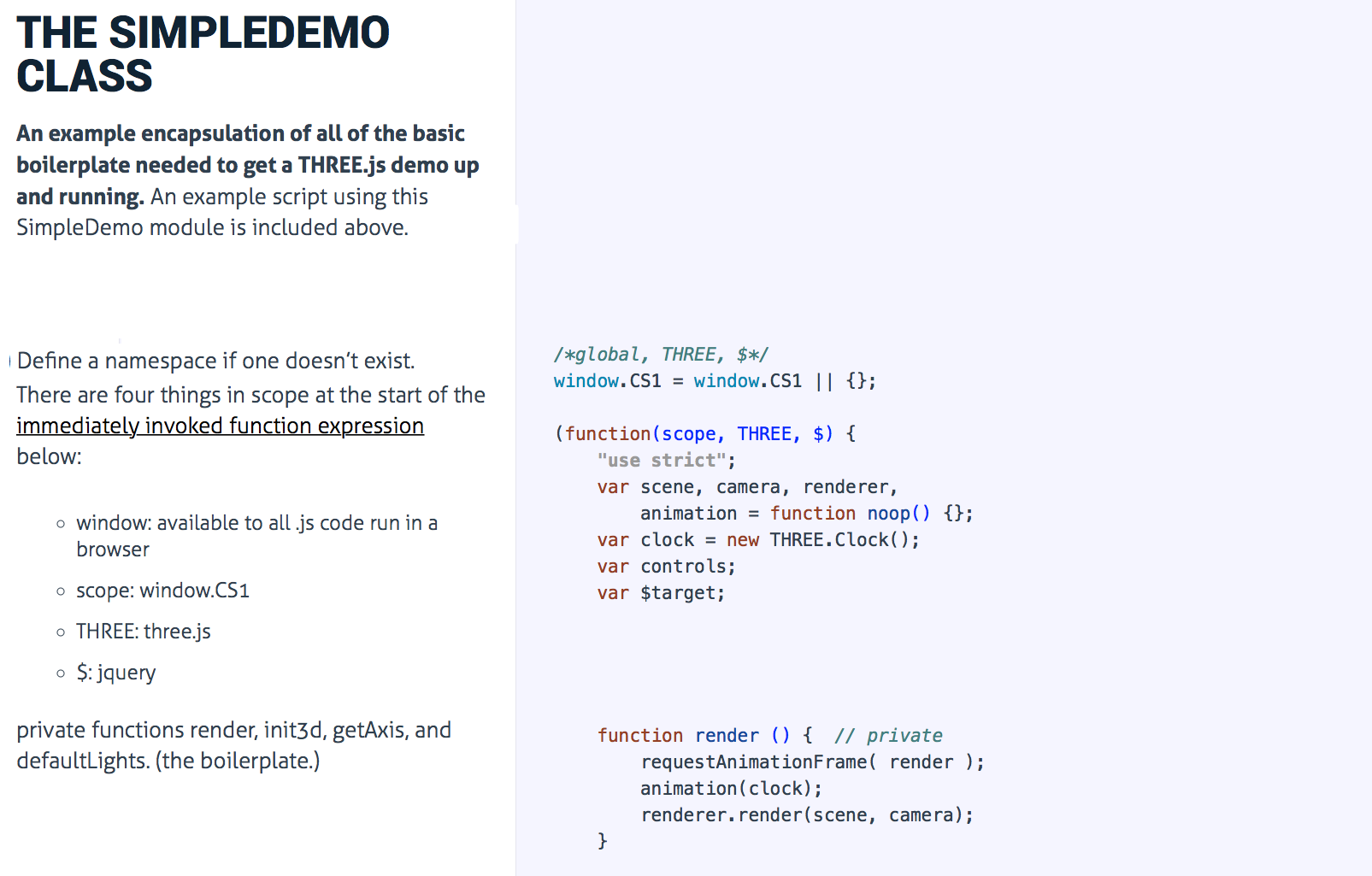

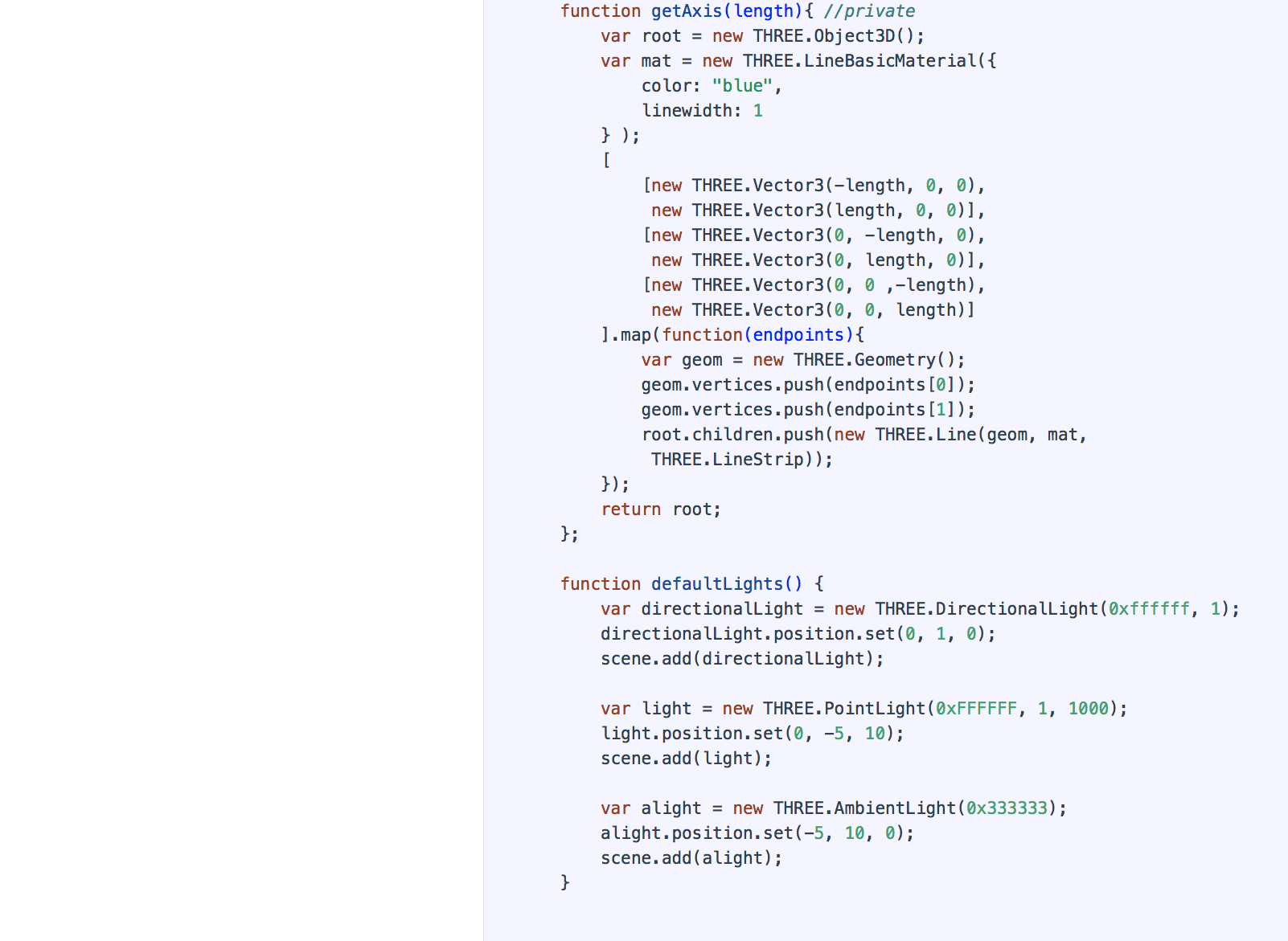

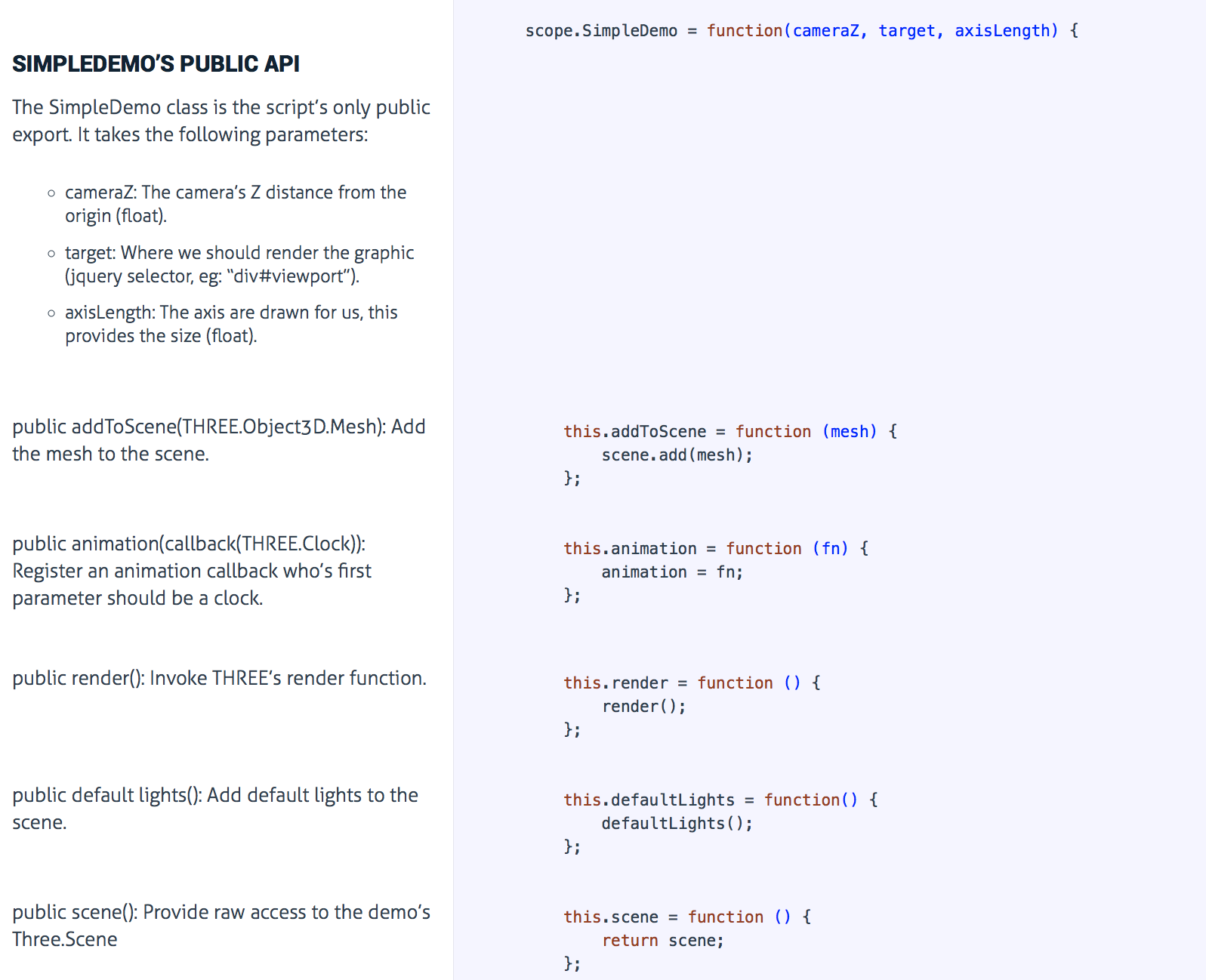

APPENDIX 1. LITERATE PROGRAMMING EXAMPLE ON SIMPLIFYING BOILERPLATE IN A JAVASCRIPT GRAPHICS LIBRARY FOR TEACHING PURPOSES

Three.js, a high level JavaScript graphics library is promising in its capacity to teach both good software engineering, and computer graphics. In it’s role as a context for teaching programming, it positions students to become competent at web applications engineering, a highly relevant mode in today’s marketplace.

Used not as a context, but as a means to understand Computer Graphics itself, Three.js is a sufficient technology for solving Computer Graphics problems. (For example, the items annotated ‘Usage’ in Computer Science Curricula 2013, Appendix A – Computer Graphics and Visualization, by ACM.)

In either case, due attention should be paid to the process of creating good maintainable solutions, if only to promote good habits in future software engineers. A challenge in this regard is that typical Three.js examples include a lot of fairly arbitrary boilerplate, and don’t hint at or inform the engineering of larger applications.

The root cause of this is likely JavaScript itself, with a tradition of ‘scripting’, a lack of scope/namespace management, and a hard to understand inheritance system that falls outside of classical object orientation being endemic to the technology. The brief code sample below represents an attempt to address these problems.

Achuthan, K., Ramesh, M. V., Punnekkat, S., & Raman, R. (2014). Internationalizing engineering education with phased study programs: India-European experience. Paper presented at the Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 2014 IEEE.

Association for Computing Machinery (2013). Computer Science Curricula 2013: Curriculum Guidelines for Undergraduate Degree Programs in Computer Science..

Bayzick, J., Askins, B., Kalafut, S., & Spear, M. (2013). Reading mobile games throughout the curriculum. Paper presented at the Proceeding of the 44th ACM technical symposium on Computer science education.

Blank, D., Kay, J. S., Marshall, J. B., O’Hara, K., & Russo, M. (2012). Calico: a multi-programming-language, multi-context framework designed for computer science education. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education.

Greenberg, I., Kumar, D., & Xu, D. (2012). Creative coding and visual portfolios for CS1. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education.

Ilinkin, I. (2014). Opportunities for android projects in a CS1 course. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 45th ACM technical symposium on Computer science education.

Necaise, R. D. (2014). EzGraphics: Python graphics for the classroom. Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges, 30(2), 192-199.

Maeda, J., & Foreword By-Antonelli, P. (2001). Design by numbers: MIT Press.

Romero, M., Thuresson, B., Peters, C., Kis, F., Coppard, J., Andrée, J., & Landazuri, N. (2014). Augmenting PBL with large public presentations: a case study in interactive graphics pedagogy. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Innovation & technology in computer science education.

Shesh, A. (2013). Toward a Singleton Undergraduate Computer Graphics Course in Small and Medium-sized Colleges. ACM Transactions on Computing Education (TOCE), 13(4), 17.

Wei, Y., & Du, C. (2014). Reform of basic computer teaching practice by enhancing computational science thinking ability. Paper presented at the Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), 2014 IEEE International Conference on.Maeda, J., & Foreword By-Antonelli, P. (2001). Design by numbers: MIT Press.

Yang, S. (2014). The Connection of Teaching and Computer to Improve the Teaching Quality. Paper presented at the 2014 International Conference on Computer, Communications and Information Technology (CCIT 2014).